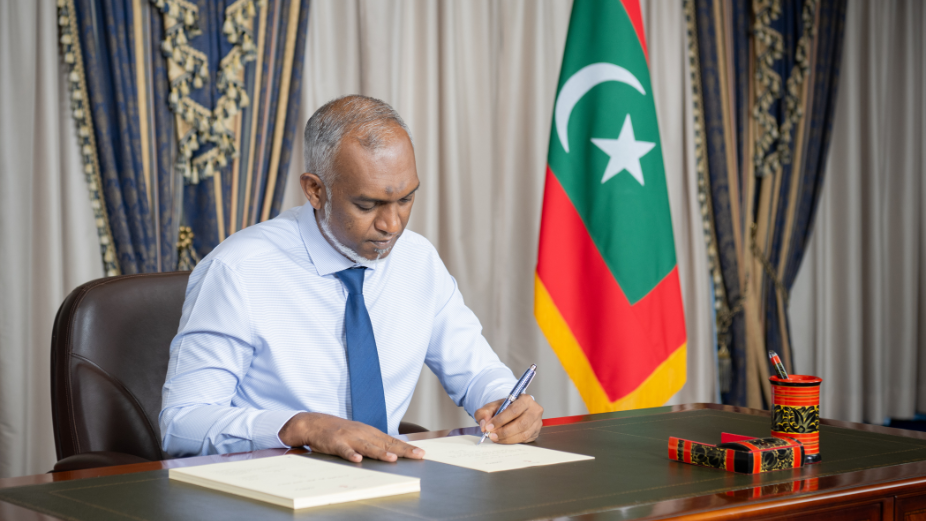

President Dr Mohamed Muizzu has ratified two pieces of legislation. The Urban Planning and Management Act (Act No. 15/2024) and the 13th Amendment to the Decentralisation Act (Act No. 07/2010) aimed at restructuring the country’s infrastructure planning and land use management. Both laws, passed by Parliament on 22 August 2024, have sparked concerns over their potential impact on local governance and democratic decentralisation in the Maldives.

The Urban Planning and Management Act mandates a comprehensive framework for infrastructure planning that seeks to sustainably maximise economic and social benefits derived from land use. Under this Act, the national policy on infrastructure planning will be determined by the President, following advisement from the Cabinet, centralising authority in the executive branch. The Ministry of Housing, Land, and Urban Development, City and Island Councils, and agencies responsible for developing urban, industrial, and special economic zones will be tasked with drafting, passing, and implementing these plans, including the issuance of land development permits. The Act, published in the Government Gazette upon ratification, is set to come into effect in six months.

Significantly, the Act stipulates that land in the Maldives may only be developed after obtaining permission in accordance with its provisions. Development standards outlined in the Act, and its subsequent regulations, must align with criteria set forth within this legislative framework, suggesting a more top-down approach to land use management.

In tandem with this, President Muizzu ratified the 13th Amendment to the Decentralisation Act on 8 September 2024. The amendment integrates the land use plans developed by City and Island Councils into the broader Physical Development Plan, as mandated by the newly ratified Urban Planning and Management Act. The amendment revises existing requirements, specifying that an island’s or city’s development plan must conform to the “Island Development Master Plan” or “City Development Master Plan” prepared by the respective councils, rather than their own independent land use plans.

While these legislative changes aim to streamline land use planning and management, critics argue they undermine the democratic principles of decentralisation. By centralising policy formulation within the President’s Office and aligning local councils’ development plans with a national framework, the Acts could dilute the decision-making authority of local councils. The move effectively shifts significant control away from local governance bodies, which were designed to reflect the needs and aspirations of their communities.

Decentralisation has been a cornerstone of governance reforms in the Maldives, intended to empower local councils and communities to shape their development trajectories. By mandating conformity to a centralised Physical Development Plan, the 13th Amendment and the Urban Planning and Management Act risk reducing local councils to administrative arms of the central government, potentially weakening the decentralisation process. Such centralisation may also limit community involvement and engagement in the planning process, eroding the democratic values that decentralisation seeks to uphold.

The broader implication of these changes points to a tension between national development goals and local autonomy. While streamlined national policies can ensure cohesive and sustainable development, the lack of autonomy for local councils in decision-making could result in policies that do not fully address local needs and priorities. This could further alienate communities and undermine the democratic processes that ensure their voices are heard.

As these laws take effect, the balance between national oversight and local autonomy will be crucial in determining the success of decentralisation in the Maldives. The government must carefully navigate this balance to ensure that the principles of democracy and decentralisation are not compromised in the pursuit of national development goals.